Contents

1.2 Research Aim and Objectives. 4

1.3 Rationale for the Study. 5

1.6 Structure of the Dissertation. 6

CHAPTER 2: LITERATURE REVIEW… 8

2.1: Evaluate Policy Alignment with International Standards. 8

2.2: Identify Systemic Issues and Gaps in Implementation. 10

2.3: Examine Ethical and Cultural Influences. 13

2.4: Evaluate the Effectiveness of Specific Child Protection Measures. 15

3.8 Validity and Reliability. 27

CHAPTER 4: DATA ANALYSIS AND DISCUSSION.. 29

4.1 Survey Interpretation and analysis. 29

CHAPTER 5: CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS. 43

CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION

1.1 Background and Context

Child protection policies affect global child safety, well-being, and development. These laws protect children from abuse, neglect, exploitation, and other harm, particularly those vulnerable due to financial hardship, parental neglect, or violence. Governments, NGOs, and international organisations defend children’s rights. One of the most significant worldwide instruments in this area is the UNCRC, which outlines the rights and protections every child has regardless of nation, background, or financial status.

Child protection is based on international organisations like the UNCRC and national laws, although loopholes exist. Underfunding, bureaucratic inefficiency, and fragmented services afflict child protection systems in industrialised nations (Grey, 2015). Low-income regions have limited resources, legal enforcement, and cultural attitudes that hinder child safety methods. Sometimes law enforcement, social services, and healthcare providers can’t intervene, allowing child abuse and neglect to continue (Powell et al., 2020).

Major issue: child protection programs lack interagency coordination. To safeguard children, social workers, healthcare experts, law enforcement, and schools must collaborate. Poor communication and resource restrictions delay or prevent child welfare initiatives (Gilbert et al., 2011). Child protection that violates family rights or culture might be unethical. Children’s rights, parental autonomy, and cultural practises are hard to reconcile in child protection programs. Given these challenges, this research investigates how successfully child protection services safeguard vulnerable children. How these rules fulfil international standards, institutional barriers to implementation, and child protection specialists’ ethics are examined. The report critically evaluates these issues to offer policies to promote child safety and worldwide child well-being.

1.2 Research Aim and Objectives

This study examines child protection policies and effectiveness in safeguarding vulnerable children.

Research Objectives

- Evaluate Policy Alignment with International Standards – Assess how successfully national child protection policies safeguard children’s rights vs UNCRC.

- Identify Systemic Issues and Gaps in Implementation – Examine child protection service resource constraints, interagency cooperation, and bureaucratic inefficiencies.

- Examine Ethical and Cultural Influences – Examine ethical issues and how culture and society effect child protection laws.

- Evaluate the Effectiveness of Specific Child Protection Measures – Examine emergency protection orders, multi-agency safeguarding, and obligatory reporting laws.

1.3 Rationale for the Study

Children are vulnerable to abuse, neglect, trafficking, and exploitation. According to UNICEF (2020), 1 billion children worldwide experience violence, underscoring the need for comprehensive and effective child protection. The UNCRC promotes child protection, survival, and development. Despite worldwide rules, many nations fail to safeguard children.

Protecting children, ensuring justice, and helping victims need child protection policies. Finance, legal enforcement, and public awareness often affect policy formulation and implementation. This studies are essential for understanding whether child protection legal guidelines are safeguarding prone youngsters or require pressing reform to suit legislative purpose with truth. Child protection structures frequently fail because of structural limitations, in spite of properly-intended legislation. Powell et al. (2020) found that social groups, law enforcement, and healthcare specialists work poorly collectively to respond to infant abuse. Silos in child welfare organizations bog down verbal exchange and choice-making. Despite legal guidelines, those systemic screw ups positioned at-risk youngsters in hazard.

Resource allocation is every other problem. Many countries lack funding for child protection organisations, making investigations, social worker training, and monitoring difficult (Munro, 2019). Underfunded and understaffed social workers ignore or postpone abuse and neglect cases. This research will examine how resource constraints and institutional inefficiencies effect child protection policies. Parental power and children’s rights are significant ethical challenges for child protection programs. When government intervention is required is a challenging child welfare ethical issue. Children and families may suffer long-term psychological and emotional impacts from these actions.

Culture and religion might collide with child safety laws, causing parenting ethical issues. Some communities practice physical punishment, but international human rights standards consider it abuse (Larcher, 2007). The study will explore how legislators and child protection agencies handle ethical issues and if current frameworks are sufficient. Culture affects child protection policy effectiveness. In certain cultures, harsh punishments may be effective parental control (Lućić et al., 2022). Legislators struggle to protect children’s rights while respecting local norms due to this cultural difference. Effective and culturally sensitive child welfare initiatives must understand how cultural beliefs impact attitudes. Children are susceptible due to socioeconomic concerns. Children in poverty are more likely to be neglected, exploited, and denied education and healthcare. Poverty might force children into work or dangerous situations. This research will evaluate how socioeconomic variables impact child protection policy and whether current solutions suit the needs of disadvantaged children.

1.4 Research Questions

To address the objectives outlined above, this research will answer the following key questions:

- How effectively do national child protection policies align with international frameworks like the UNCRC?

- What systemic barriers hinder the successful implementation of child protection policies?

- What ethical dilemmas arise in enforcing child protection laws, and how can they be addressed?

1.5 Research Methodology

It will analyse child protection policies’ effectiveness using mixed methodologies. Methodology includes:

- Policy Analysis: Reviewing child protection laws and comparing them with international standards.

- Case Studies: Examining real-life examples such as the Baby K case in the UK to understand practical challenges in policy implementation.

- Interviews with Stakeholders: Engaging with child protection officers, social workers, and policymakers to gain insights into systemic barriers and ethical concerns.

- Quantitative Data Analysis: Assessing statistical data on child welfare indicators to evaluate policy impact.

In-depth qualitative and quantitative study will assess child protection systems.

1.6 Structure of the Dissertation

This dissertation is structured as follows:

| Chapter 1: Introduction | This chapter discusses the research topic, relevance, questions, aims, and framework. |

| Chapter 2: Literature Review | Child protection policy literature on international frameworks, systemic problems, ethics, and culture. |

| Chapter 3: Methodology | A discussion of the research approach, data collection methods, and analytical techniques used in the study. |

| Chapter 4: Policy Evaluation and Case Studies | Comparing national child protection policies using UNCRC criteria and detailed case studies. |

| Chapter 5: Ethical and Cultural Considerations | A discussion of key ethical issues and cultural factors that impact child protection effectiveness. |

| Chapter 6: Findings and Discussion | Presentation of research findings and analysis of key themes emerging from the data. |

| Chapter 7: Conclusion and Recommendations | Summary of key findings, policy recommendations, and suggestions for future research. |

1.7 Conclusion

Though child protection is a human right, policy and operational failures put countless children at risk worldwide. This research evaluates child protection framework strengths and weaknesses, examines systemic, ethical, and cultural factors, and suggests policy theory-practice improvements. The report’s comprehensive study will impact global child protection discussions and policy changes to safeguard vulnerable children.

CHAPTER 2: LITERATURE REVIEW

2.0 Introduction

This chapter analyses child protection law and practice. The major objectives are to align child protection policies with international standards, uncover systemic faults and implementation gaps, assess ethical and cultural aspects, and assess specific protective measures. This chapter uses academic, legal, and case studies to assess child protection methods’ pros and cons. The review prepares for analysis by identifying theoretical perspectives and empirical evidence that impact global child protection initiatives.

2.1: Evaluate Policy Alignment with International Standards

Child protection against abuse, neglect, exploitation, and violence is a worldwide legal issue. These include the 1989 “United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC),” which protects, develops, and well-being children. This chapter critically evaluates national child protection policies’ international conformance.

2.1.1 Overview of the UNCRC and International Norms

The most comprehensive international child rights document is the UNCRC, approved by 196 governments (UNICEF, 2021). Article 2 prohibits discrimination, Article 3 protects the child’s best interests, Article 6 guarantees life, survival, and development, and Article 12 guarantees respect for the child’s views. According to Ndondo (2024), every legal and policy framework must include these elements to meet global child protection requirements. Article 19 of the UNCRC requires state parties to take legal, administrative, and pedagogical measures to protect children from any abuse, whereas Article 34 covers sexual exploitation. Tanveer (2024) emphasises that the agreement requires national legislation and initiatives to implement child welfare beyond lip service.

| Article | Description |

| Article 2 | Prohibits discrimination against children based on any grounds. |

| Article 3 | Protects the child’s best interests in all actions concerning them. |

| Article 6 | Guarantees the child’s right to life, survival, and development. |

| Article 12 | Guarantees respect for the child’s views in all matters affecting them. |

| Article 19 | Requires states to take measures to protect children from abuse and neglect. |

| Article 34 | Covers protection from sexual exploitation and abuse. |

2.1.2 National Policy Alignment with the UNCRC

Many states acknowledge UNCRC, but its actions differ. Collins and Wright (2011) propose that cultural, political, and economic barriers hinder many countries from passing child protection legislation. The Children Act 1989 and Children and Families Act 2014 matched UK legislation with UNCRC. These rules promote UNCRC ideals including child protection and participation, according to Winter et al. (2024).

Implementation varies among countries. UK austerity has weakened UNCRC-aligned child protection services, according to Islam (2024). Although it has recognised some UNCRC provisions in principle, the US is the only UN member not to ratify it. Schröder (2025) notes that political ideology rather than international best practices has caused state-by-state child protection differences. Low- and middle-income countries’ alignment is symbolic. Although child protection measures exist, Kišūnaitė and Bui (2021) discovered that insufficient legislative enforcement and sociocultural norms hamper their successful implementation in Sub-Saharan Africa. Many institutions apply outdated colonial laws that violate child rights.

2.1.3 Challenges in Policy Alignment

Interpreting and applying the ‘best interests of the child’ premise is necessary to align national policy with international norms. Though crucial to the UNCRC, this notion is subjective. According to Forde (2021), countries may inconsistently adopt this principle, resulting in biassed or culturally inappropriate treatment.Decentralisation of child protection services is another concern. Schröder et al. (2025) observe that national governments sometimes delegate responsibilities to regional authorities or NGOs, which may cause policy inconsistencies. Fragmentation hampers international standardisation. Mismatched language and vocabulary in state law may confuse UNCRC intent. National laws utilise “reasonable chastisement” notwithstanding the UNCRC’s prohibition on physical punishment. Islam (2025) alleges legal inadequacies allow abusive techniques to persist under the guise of punishment, violating international law.

2.1.4 Progress and Best Practices in Policy Alignment

Despite problems, some nations fit with international frameworks well. Sweden was the first to abolish all child physical punishment in 1979, under the UNCRC. Winter (2024) reports that Sweden’s early adoption of a child-centered protection approach reduced child maltreatment and raised knowledge of children’s rights.

Norway and New Zealand have also included child rights into policy. The Vulnerable Children Act 2014 in New Zealand mandates governmental agencies safeguard children in accordance with the UNCRC. Collins and Wright (2022) say this legislation is a paradigm for nations trying to operationalise international norms nationally. Tanveer’s (2024) Child Protection Index helps analyse country UNCRC compliance. Romania and Georgia have utilised this technology to discover gaps and modify laws and services.

2.1.5 Role of Monitoring and Accountability

International standards need strict monitoring and reporting. States must report to the CRC under UNCRC Article 44. Collins (2022) notes that many governments report late or incompletely. Lack of civil society and independent scrutiny lowers accountability.

Child Rights Effect Assessments (CRIAs) are also being used to evaluate new laws’ effects on children. Winter et al. (2024) propose that nations must incorporate CRIAs in policymaking to accomplish UNCRC aims.

2.1.6 Gaps Between Legal Compliance and Practical Outcomes

International compliance and children’s experiences can vary. Laws may be UNCRC-compliant, but underfunding, unqualified personnel, and inadequate data collection hurt protection. Child-focused approaches need structural support, according to Forde (2021). Legal alignment without this is symbolic, not transformative. The UNCRC recommends meaningful child participation in policymaking, however Schröder et al. (2025) say it seldom occurs. Exclusion compromises policy alignment and execution.

2.2: Identify Systemic Issues and Gaps in Implementation

Many governments fail to implement comprehensive child protection frameworks due to financial limits, poor interagency collaboration, and bureaucratic inefficiency. The chapter shows how these obstacles impair child protection services, revealing a substantial gap between statutory intent and reality.

- 2.2.1 Resource Constraints in Child Protection Services

Insufficient funding and staff hinder child protection. Colvin (2021) claims resource constraints impair treatment quality, leaving at-risk children untreated. Child protection agencies struggle to prevent and respond to abuse due to budget restrictions, huge caseloads, and insufficient training.

Marino and Wright (2022) allege that austerity-driven public budget cuts, particularly in the UK, have greatly reduced local authority child welfare. Crisis reaction replaces prevention due to underfunding. According to Dollee (2021), residual welfare countries—intervening only in severe cases—are more prone to systemic failures due to underinvestment in early support programs.

Low- and middle-income countries suffer from economic instability and competing interests. Steive (2024) states that certain African countries spend less than 1% of GDP on child welfare, leaving whole regions unserved. Laegreid and Rykkja (2022) warn that informal care arrangements or unregulated services might lead to neglect and exploitation due to limited resources.

- 2.2.2 Workforce Capacity and Training Gaps

Policy implementation is critical for child protection professionals. However, inadequate training and turnover reduce care quality. According to Jolles et al. (2022), high workloads, emotional stress, and lack of support burn out social workers, resulting in inefficiency and inconsistent decision-making. Training matters too. Rai and Shekhar (2023) found that many frontline workers lack child development, trauma-informed care, and cultural competence training. This inhibits their ability to examine complex challenges and collaborate with other industries. One-time training in many systems creates skill gaps (Griffiths, 2022).

- 2.2.3 Interagency Cooperation: Fragmented Systems

To protect children, social services, health, education, and law enforcement must collaborate. Interagency collaboration remains poor. Jolles et al. (2022) say confusing duties, processes, and data-sharing mechanisms duplicate or lose intervention opportunities.

Laegreid and Rykkja (2022), commissioned following Victoria Climbié’s UK death, discovered serious agency communication and information sharing difficulties. Every Child Matters and Working Together to Safeguard Children assist, yet gaps persist. Jolles et al. (2022) say poor cooperation between statutory institutions lets youngsters fall between the cracks.

International service delivery structure differences exacerbate these issues. Depending on the country, health or social development ministries or judicial ministries handle child protection, generating administrative issues. According to Steive et al. (2024), fragmentation limits system responsiveness by conflicting priorities and compartmentalising activities.

- 2.2.4 Bureaucratic Inefficiencies and Administrative Delays

Bureaucracy in child protection systems may delay vital answers and destroy public trust. Paperwork and reporting often prevent social workers from helping children and families, according to Dollee (2021). The system values compliance above care. Many countries need many approvals for child protection decisions, delaying abuse or neglect responses. Munro and Wright (2022) say bureaucratic institutions’ risk-aversion, fear of responsibility, and excessive formality hinder professional judgement. This protective culture slows innovation and intervention. Technology for case management is usually outdated or incompatible across departments. According to Colvin et al. (2021), UK systems often fail to combine child protection databases with health or school information, hindering holistic evaluations. Lack of digitalisation in developing countries makes case tracking more difficult and error-prone.

- 2.2.5 Policy-Implementation Gaps

Even internationally recognised policies are seldom enforced. Dollee (2021) defines a “policy-implementation gap” as legislation without operational frameworks, money, or monitoring. A government may ban physical punishment but not train teachers and parents on alternatives, rendering the law worthless. Steive et al. (2024) attribute this gap to systemic dysfunctions such unclear accountability, poor leadership, and political indifference. Inconsistent and unequal child protection is provided by underfunded local governments or NGOs when government priorities are not met.

- 2.2.6 Data and Monitoring Weaknesses

Planning, monitoring, and changing child protection programs need trustworthy data. Many countries lack child abuse, aid, and outcomes data. Marino and Wright (2022) say administrative data has little policymaking relevance. Jolles et al. (2022) frequently encourage countries to strengthen child protection data systems. Without evidence-based service planning, systemic issues remain hidden. National child protection information systems that connect agencies and allow real-time case management are needed, particularly in nations with significant child vulnerability, according to Griffiths (2022).

- 2.2.7 Marginalised and At-Risk Groups

Ethnic minorities, handicapped children, and alternative care children suffer structural issues. Rai and Shekhar (2023) argue child protection authorities overlook these children due to institutional bias or lack of tailored help. Due to institutionalisation and stigma, Laegreid and Rykkja (2022) found that residential children get lower-quality protective services. Steive et al. (2024) propose that communication issues and attitudinal biases make disabled children more likely to be mistreated but less likely to be believed or followed up.

2.3: Examine Ethical and Cultural Influences

Ethics, culture, and society affect child protection legislation and initiatives. It shows how morality, religion, norms, and society affect child abuse, interventions, and legislation.

- 2.3.1 Ethical Foundations of Child Protection

Safeguarding children’s rights and dignity is moral. Soelton et al. (2023) say healthcare and social welfare ethics are based on autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficence, and fairness. All children must be treated equally (justice), their views heard (autonomy), and their best interests served (beneficence). Professional obligations might collide with familial, legal, or cultural values, generating ethical dilemmas. Adams (2023) states that social workers must balance family privacy and abuse reporting, generating ethical problems. Taking a child from their family may cause sorrow and raise moral considerations about government overreach.

Saxena et al. (2021) emphasises the ethical need of considering children as rights-holders rather than passive recipients of adult protection. The 1989 UNCRC ensures children’s engagement, protection, and provision. In patriarchal or authoritarian societies that despise children, these rights are hard to implement.

- 2.3.2 Cultural Relativism vs Universal Child Rights

Conflict between fundamental human rights and cultural relativism threatens child protection. The UNCRC promotes global child welfare, yet diverse cultures define childhood, parenting, and punishment. Universal child protection frameworks often collide with cultural norms, De Bie et al. (2023) found. Despite Western bans, corporal punishment is popular in Africa, Asia, and the Middle East. Du and Xie (2021) say over 60 countries authorise home-based corporal punishment. Many societies explain such practices with tradition, religion, or parental rights.

According to Katirai (2024), these norms may hinder protective legislation acceptance or implementation. Brendel et al. (2021) argue that Western child protection measures without cultural sensitivity are ineffective or detrimental. Occasionally, collaborative parenting confronts Western nuclear families. A child removed from extended family may clash with culture and generate conflict.

- 2.3.3 Ethical Challenges in Cross-Cultural Interventions

Multicultural practitioners encounter ethical issues in cross-cultural therapies. Fernando (2010) says experts may face houses with forced marriage, FGM, or child labour. Though culturally accepted, these behaviours often violate children’s rights.

Killen and Dahl (2021) emphasise cultural competence—understanding, respecting, and working within a family’s culture while maintaining child safety. Practitioners must tread cautiously to protect vulnerable children and avoid cultural imperialism. In the UK, safeguarding workers are taught to detect FGM indicators and involve communities via culturally relevant awareness initiatives. Alwahaby et al. (2022) say combining legal enforcement with education and cultural discourse is ethical and more effective than punitive measures.

- 2.3.4 Societal Norms and Gender Roles

Family, gender, and early views influence child safety. Boy privilege in patriarchal societies may cause teenage marriage, abuse, and cruelty to women. Katirai (2024) claims gender-biased policies harm girls worldwide.

According to Du and Xie (2021), hegemonic masculinity normalises child maltreatment, particularly against boys, as punishment or character-building. Society may see abuse as socialisation. Child labour is essential in certain societies owing to poverty, making protective measures challenging. According to De Bie et al. (2023), child safety should address cultural norms including violence, gender equality, and authority. They believe social education must accompany legislative improvements to transform attitudes and help children.

- 2.3.5 Religion and Ethical Dilemmas in Child Welfare

Religion greatly impacts child parenting and discipline. Religion may encourage parental control or physical punishment. Religiously conservative U.S. households were more likely to utilise physical punishment because they believed it was divinely sanctioned. Saxena et al. (2021) say religious beliefs may clash with medical or legal treatment. Religious refusals of life-saving blood transfusions show the delicate balance between parental rights, religious freedom, and child welfare. Religion can protect. Religious NGOs provide vital child care services to neglected populations. Religious leaders promote child protection reform and bridge ethical gaps, argue Adams et al. (2023).

- 2.3.6 Legal Pluralism and Customary Law

In many locations, statutory and customary rules impede child protection enforcement. Customary courts may handle child cases using local customs instead than legislation. This may provide inconsistent outcomes and undermine formal legal protections, say Soelton et al. (2023). In certain African villages, elders may decide child custody or abuse issues without child welfare. In circumstances of familial abuse, these decisions may prioritise family or community above the kid.

- 2.3.7 Migration, Identity, and Cultural Dislocation

Refugee and migrant children face ethical and cultural difficulties. Their cultures may have different parenting, family, and child autonomy norms. According to Soelton, et al. (2023), host country child protection agencies often fail to address these children’s cultural needs, fostering alienation and mistrust. Children in irregular migration or unlawful status are often excluded from child safety programs. Adams, et al. (2023) argue that this exclusion violates children’s rights and is unethical. Insensitive responses like placing children in foster care without community input or neglecting their language and values may create further pain. Saxena, et al. (2021) found that culturally sensitive strategies like ethnic community groups improve outcomes and ethics. Ethics and culture shape child protection laws.

2.4: Evaluate the Effectiveness of Specific Child Protection Measures

To safeguard vulnerable children, child protection has evolved. Scholarly sources, policy assessments, and case studies will be used to critically evaluate Emergency Protection Orders (EPOs), multi-agency safeguarding systems, and reporting rules. The UK, Australia, and US child protection laws and practices depend on these interventions.

2.4.1 Emergency Protection Orders (EPOs)

Emergency Protection Orders (EPOs) quickly safeguard susceptible youngsters. Courts provide children temporary custody to local authorities or other safe organisations for up to eight days in De Bie, et al. (2023). These orders allow police to immediately remove children from unsafe situations without parental consent. Effectiveness of EPO has been commended and questioned. Du and Xie (2021) propose that EPOs protect children promptly as legal protections. According to family court instances, timely removal usually stopped physical abuse or neglect from increasing. According to Katirai (2024), hurried solutions may ignore the emotional toll of abrupt family separation. Moral dilemmas arise when balancing child protection and family. EPO application inconsistencies are shown in case studies. Re X (2006): Emergency Protection Orders EWCA Civ 126 suggests courts are wary of EPOs without evidence. Judicial discretion must weigh urgent harm to parental rights, according to Brendel et al. (2021). Without complete social support, EPOs operate in crises but have unknown long-term consequences.

2.4.2 Multi-Agency Safeguarding

Social workers, police, healthcare providers, and educators collaborate on multi-agency safeguarding. Comprehensive review and intervention are needed for child welfare concerns. To combat systemic failures like Victoria Climbié’s, England created Local Safeguarding Children Boards (LSCBs) under the Children Act 2004. Killen and Dahl (2021) underlined agency responsibility, communication, and accountability in their Climbié fatality inquiry. His findings criticised siloed child protection systems for overlooking warning signs. Alwahaby et al. (2022) found that interprofessional training and information-sharing procedures boosted early child danger identification.

Effective cooperation is still tough. Soelton et al. (2023) say institutional hierarchies, professional standards, and role definitions limit cooperation. The Baby P tragedy (Peter Connelly, 2007) illustrated how companies failed to communicate. Adams, et al. (2023) advised letting specialists make decisions rather than following procedures. Instead, Western Australia’s Signs of Safety worked. Saxena, et al. (2021) suggest using strengths-based family interactions and collaborative risk assessments to increase engagement and minimise care placements. Multi-agency frameworks provide benefits, but leadership, training, and culture matter.

2.4.3 Obligatory (Mandatory) Reporting Laws

Mandatory reporting laws require teachers, doctors, and social professionals to report suspected child abuse or neglect. These laws say early discovery increases protection. De Bie, et al. (2023) noted US mandatory reporting has revealed hidden maltreatment, especially in homes where children are silenced. Australian state reporting standards vary, but the concept is the same. Mandatory reporting in New South Wales boosted child protection alerts, according to Du and Xie (2021). However, not all abuse allegations are proven, causing resource allocation and investigation overload issues. Mandatory reporting promotes accountability, but Katirai (2024) says it may overload child protection agencies with low-risk instances. Better training and guidelines are needed since professionals may over-report to avoid responsibility or under-report to avoid confidentiality, according to Brendel, et al. (2021). The 2012 UK Daniel Pelka case shows the necessity and weaknesses of reporting methods. Abuse was seen by teachers, but confusing criteria and school policies delayed escalation. Killen and Dahl (2021) supported transparent reporting and professional investigation after the Serious Case Review. Comparisons between nations show best practices. Even without mandatory reporting, Scandinavian countries prioritise prevention via family welfare institutions, according to Alwahaby et al. (2022).

2.5 Theoretical Review

Child protection policy, practice, and evaluation are influenced by law, process, and theory. This theoretical test will cover child protection emergency protection orders (EPOs), multi-agency safeguarding, and required reporting laws. Systems, Ecological, Rights-Based, and Theory of Planned Behaviour describe socio-legal intervention structure and function.

- 2.5.1 Systems Theory

The Ludwig von Bertalanffy-developed Systems Theory can analyse child protection procedures (McGuire, et al 2021). According to the theory, legal, social, education, and healthcare subsystems work together to maintain system stability.

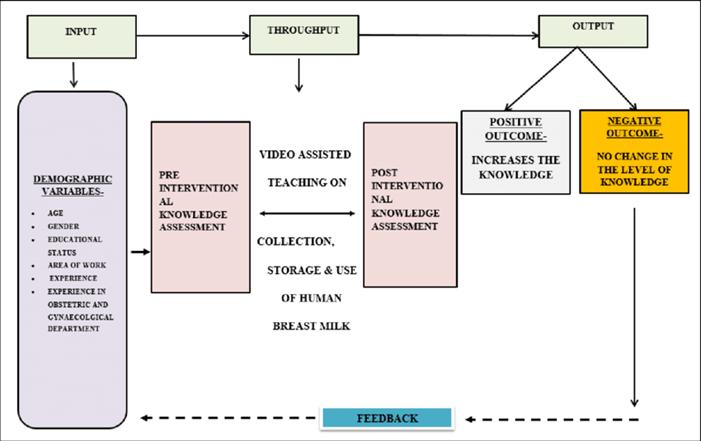

Figure 1 Systems Theory

(Source: Shinde, and Mahadalkar, 2018)

Ball et al. (2024) believe that subsystems promote multi-agency child safety by communicating and working together. These subsystems fail in high-profile cases like Baby P and Victoria Climbié, diminishing the child’s protective net.

Systems Theory also criticises EPOs. EPOs respond, but their sudden arrival without wrap-around services may disturb family and systemic equilibrium. McManus, et al. (2023) say legal activation and the child’s ecosystem—housing, counselling, education, and community support—make an EPO successful.

- 2.5.2 The Ecological Model of Child Development

Urie Bronfenbrenner’s 1979 Ecological Model of Child Development is extensively used in child protection studies. The microsystem (family), mesosystem (school/community), exosystem (extended family, neighbours), and macrosystem (culture, law, economics) impact a child’s development.

Figure 2 The Ecological Model of Child Development

(Source: Buys, and Gerber, 2021)

This model explains why mandatory reporting and multi-agency protection need many layers. Mandatory reporting lets teachers and physicians report microsystem misuse. Reporting requires adequate exosystem response—child protection agencies, legal systems.

Without ecology-level collaboration, Gardner Asker (2024) thinks interventions may only have short-term effects. The Daniel Pelka case highlights what happens when early abuse signals are ignored, disrupting ecological equilibrium.

- 2.5.3 Rights-Based Theory

Rights-Based Theory argues that children are autonomous rights-holders and advocates child protection. International accords like the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child support this strategy. Andrews (2023) recommends assessing child protection measures for procedural efficiency and compliance with essential rights including safety, education, and family life. Emergency Protection Orders should be considered in light of UNCRC Article 9, which states that children should not be taken from their parents unless it is in their best interest.

McGuire, et al. (2021) highlights child voices in multi-agency protection planning. Protective measures may be unempowering without kid input. Rights-Based Theory encourages fair, transparent, and participatory child protection.

- 2.5.4 Theory of Planned Behaviour

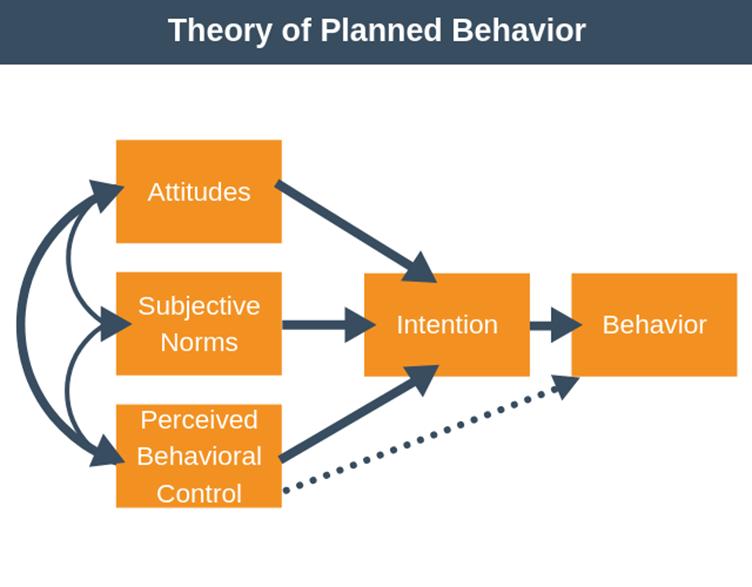

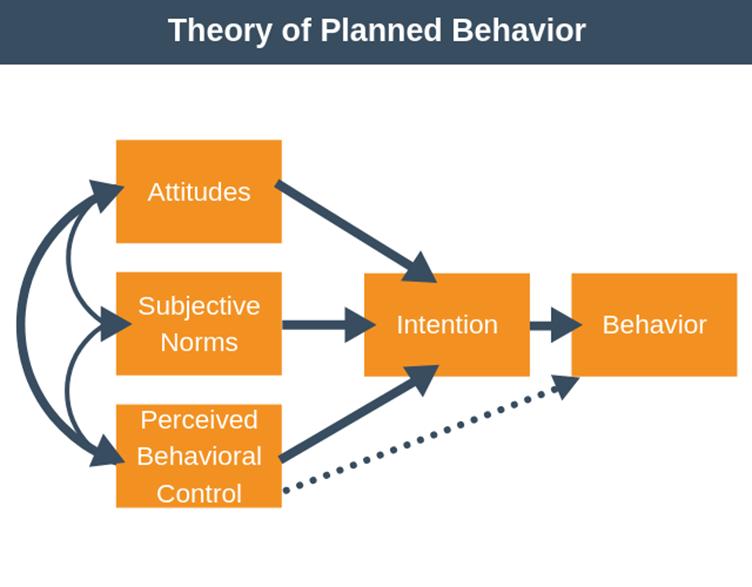

The Theory of Planned Behaviour (Ajzen, 1991) explains why mandatory reporting may fail. This hypothesis claims that attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioural control affect behaviour intention. This method was used to analyse teachers’ and healthcare workers’ abuse reporting options by Ball et al. (2024). They found that although legal requirements exist, professionals’ reporting activity is heavily influenced by whether they see meaningful repercussions (perceived control) and if they expect organisational help.

Figure 3 Theory of Planned Behaviour

(Source: Denis, 2025)

The variation in required reporting legislation compliance between areas and professions is explained by this idea. Training, peer support, and company culture shape reporting. Therefore, legal mandates must be accompanied by behavioural intention interventions, not merely statutory responsibility.

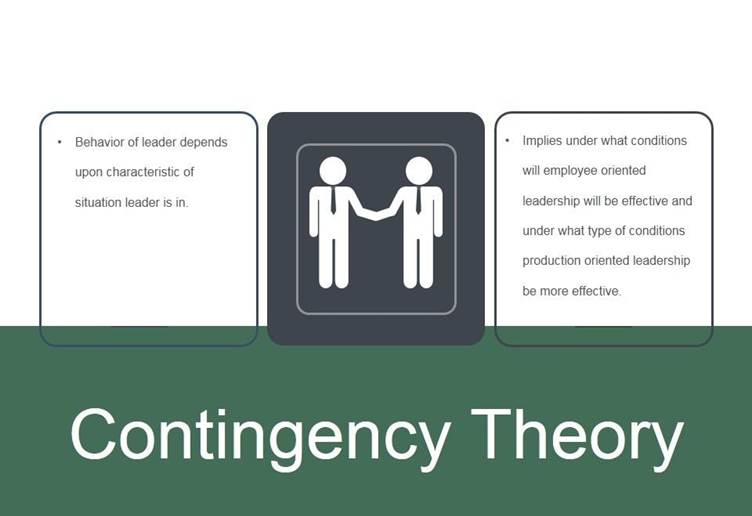

- 2.5.5 Contingency Theory in Policy Implementation

Donaldson’s Contingency Theory asserts that policy execution is not one-size-fits-all. Children protection measures like EPOs and obligatory reporting rely on organisational fit, resource availability, and context-specific elements.

Figure 4 Contingency Theory

(Source: Slide Geeks, 2025)

Emergency removal is followed by social aid, therefore EPOs may operate in nations with well-resourced child protection agencies. Such directions may generate long-term child instability in underfunded settings. McManus, et al. (2023) found that environment determines whether a child protection system is prevention-based (Scandinavian models) or intervention-based in a 10-country comparative study. This approach prioritises adaptive child protection above legal conformity without context. This theoretical review highlights child protection’s necessity for robust theoretical foundations. The Ecological Model and Systems Theory promote connectivity and multi-level engagement. According to Rights-Based Theory, practitioners and policymakers should protect children’s autonomy and dignity. The Theory of Planned Behaviour explains how human factors impact reporting law compliance, whereas Contingency Theory promotes flexible implementation.

CHAPTER 3: METHODOLOGY

3.0 Introduction

This dissertation’s methodology chapter outlines the research approach, technique, and data collection techniques used to evaluate child protection programs’ effectiveness in safeguarding vulnerable children. This research collects, analyses, and interprets data using qualitative and quantitative methods (Leech, et al., 2010). The research examines policy congruence with international standards, systemic gaps, and ethical and cultural effects on child protection procedures using qualitative interviews and quantitative questionnaires.

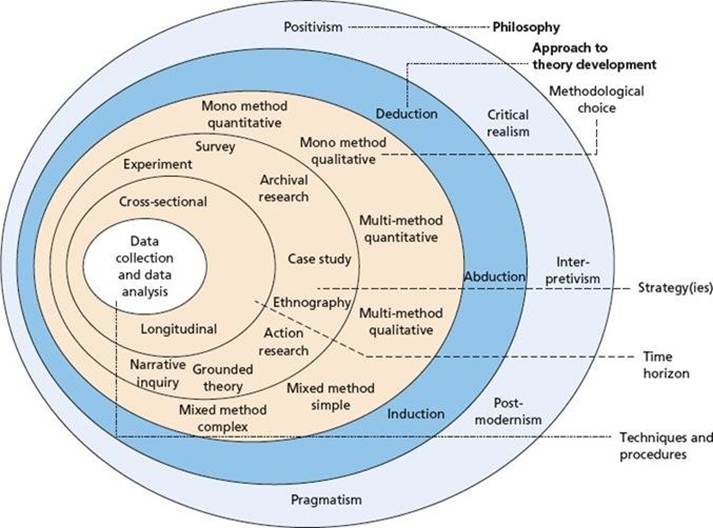

Figure 1 Saunders Research Onion framework

(Source: Mbedzi et al., 2021)

According to Sahay (2016), Saunders Research Onion framework guides the study’s design. Layers of the Research Onion indicate research options. They coordinate and justify research choices. This chapter describes the Research Onion’s philosophy, strategy, design, approach, data collecting, analysis, validity, and reliability for this research.

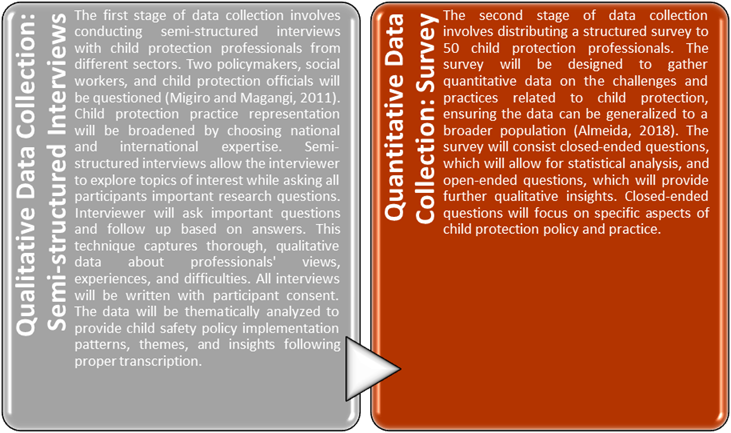

3.1 Research Procedure

The research procedure is designed to guide the collection of data through a systematic process of interviews and surveys, followed by a thorough analysis. The research will be conducted in two distinct stages: qualitative data collection through semi-structured interviews and quantitative data collection via a survey.

Figure 2 Research Procedure

(Source: By author)

Following the completion of both qualitative and quantitative data collection, the researcher will analyze the data from both methods to ensure triangulation, allowing for a more comprehensive understanding of the effectiveness of child protection policies and practices.

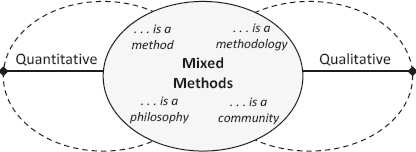

3.2 Research Design

The research adopts a mixed-methods research design, combining both qualitative and quantitative approaches to provide a rich, nuanced, and comprehensive understanding of child protection policies. This method enables the researcher to research the examine subject matter in numerous dimensions, exploring child protection procedures’ intricacies and extracting generalizable conclusions from a bigger sample. The examine integrates both forms of records to deal with baby protection worries from specialists’ lived experiences to systemic problems and limitations (Ivankova and Creswell, 2009).

Figure 3 mixed-methods research

(Source: Plano Clark and Ivankova, 2016)

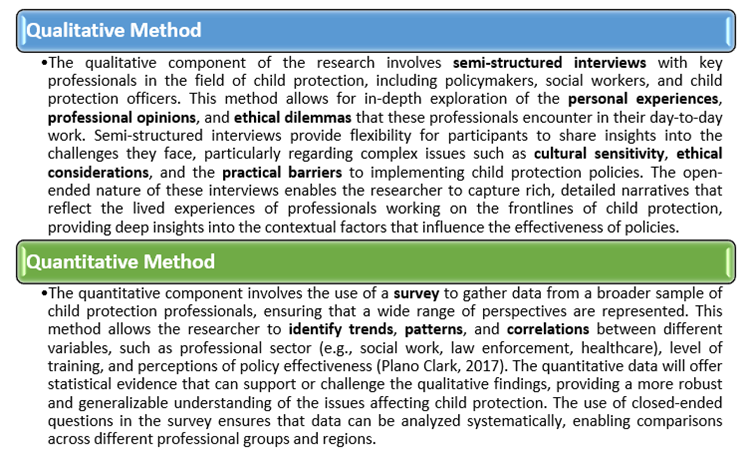

- Qualitative Research: Semi-structured Interviews

The qualitative studies will include semi-structured policymaker, social employee, and child protection officer interviews. Semi-dependent interviews may additionally address delicate subjects along with child safety system ethics, cultural sensitivity, and structural limitations. While asking fundamental questions, this interview style allows individuals brazenly communicate their experiences and mind. This approach will assist the researcher understand baby protection specialists’ issues and views. Conversational interviewing allows the researcher to explore policy implementation, moral dilemmas, and systemic troubles’ effects on regular life. Semi-dependent interviews allow for a better investigation of every participant’s attitude on infant safety (Doyle, et al., 2009).

- Quantitative Research: Survey

The quantitative studies will survey 50 social work, law enforcement, and schooling child safety specialists. The survey will quantify infant safety issues along with incidence, coverage effectiveness, and useful resource allocation’s impact. Closed-ended questions provide quantitative facts for statistical analysis, yield qualitative insights. Closed-ended questions will let the researcher discover developments and patterns across expert sectors and evaluate group responses. A thorough survey will become aware of commonplace hurdles and have a look at their consistency across more specialists, boosting infant protection expertise (Schensul & LeCompte, 2012).3

3.3 Research Philosophy

The research is grounded in a pragmatic research philosophy, which prioritizes the practical application of research findings to address real-world problems. Pragmatism emphasizes evidence-based solutions to complex problems, making it suitable for our study. Practicality in this research assesses child safety strategies for vulnerable youngsters and gives real-world recommendations.

Pragmatism makes use of qualitative and quantitative techniques since exclusive studies concerns want specific information and evaluation. This flexibility lets in the researcher to pick out the most appropriate methods primarily based at the observe’s pursuits, assuring thoroughness and topical edition. A blended-strategies method to infant protection that considers ethical, cultural, structural, and criminal factors works high-quality. Qualitative interviews and quantitative surveys display deep non-public experiences and massive statistical tendencies (Creswell, et al., 2004). The pragmatic mentality helps the studies enhance kid protection systems with practical conclusions. Focusing on real-international programs allows the research to cope with policy implementation gaps and advocate progressed child safety. Pragmatism is the finest philosophical technique for this topic since it emphasizes sensible responses.

3.4 Research Approach

The research approach used in this study is a blended-methods technique, combining both inductive and deductive reasoning. This mixture guarantees a comprehensive exploration of the study’s problem, permitting the researcher to discover new insights and test existing theories.

- Inductive Approach (Qualitative Component)

Qualitative researchers become aware of topics and ideas in records inductively. The researcher will interview toddler safety personnel semi-based approximately their thoughts, reviews, and difficulties. Data collection the use of inductive methods exhibits unexpected patterns and insights. It inspires new thoughts on structural, ethical, and cultural worries in infant protection, making it perfect for complex conditions. Researchers might also discover new ideas or beautify present ones the usage of real-global information.

- Deductive Approach (Quantitative Component)

In assessment, quantitative studies deductively examines hypotheses. The examine tackles cultural, structural, and moral issues in baby protection coverage from the literature (Kesner, 2008). The take a look at will verify infant protection experts’ concerns and present guidelines the use of a structured survey with closed-ended questions. The deductive approach employs records to assist or refute qualitative findings.

3.5 Research Choice

This Research makes use of combined-strategies, gathering qualitative and quantitative records. This technique captures both experts’ subjective experiences and subject-wide tendencies to provide a completer and extra nuanced photograph of infant protection laws and procedures. The research provides a multi-dimensional view of toddler protection’s complications and practitioners’ problems implementing exact rules by merging each methodologies (Alexander, et al., 2008).

3.6 Research Method

This research utilizes both qualitative and quantitative methods for data collection, ensuring a comprehensive approach to evaluating child protection policies.

- Semi-structured Interviews

Semi-structured interviews with two policymakers, social workers, and child protection officers will compose the qualitative component. Volunteers with child safety expertise will be thoroughly screened. Semi-structured interviews are flexible and ordered, with research-related questions. This helps researchers explore particular topics and let individuals share their opinions and experiences (Gilbert, 2006). Further questions will probe responses to better understand the challenges professionals face in executing child safety policies. Researchers may adapt to the debate and acquire nuanced and context-specific information using the semi-structured technique.

- Surveys

A quantitative study of 50 child protection practitioners from various fields is included. A poll will comprise open-ended and closed-ended questions. Closed-ended questions give quantitative data for policy effectiveness, systemic barriers, and professional issues statistical analysis (Lukens, 2007). Participants may contribute their experiences and perspectives using open-ended questions for qualitative insights. Electronic dissemination lets specialists from various fields and businesses take the survey. The research will properly assess child protection policies using in-depth human tales and statistical data.

3.7 Data Analysis

Qualitative and quantitative data will be analyzed separately to guarantee optimal assessment. This dual method enables the researcher extensively investigate the study topic.

- Qualitative Data Analysis

Semi-structured interview qualitative data will be transcribed and evaluated thematically. Data themes, ideas, and patterns are identified and categorised using thematic analysis. This strategy will help the researcher understand child protection professionals’ obstacles and systemic concerns that impact policy implementation (Fetters, et al., 2013). The investigation will also examine how ethics and culture affect child protection decisions. The researcher may find repeating themes and ideas that illuminate child protection methods by classifying and categorizing interview data.

- Quantitative Data Analysis

Survey quantitative data will be evaluated using descriptive statistics. To summarize replies and find trends, frequency distributions, percentages, and means, medians, and modes will be calculated. Cross-tabulations will evaluate correlations between factors including professional sector (e.g., social work, law enforcement, healthcare), perceived policy implementation hurdles, and child protection resources. Data will be analysed statistically using suitable tools for accuracy and efficiency (Bulsara, 2015).

The researcher may triangulate results by integrating qualitative and quantitative data analysis to better understand child protection policy success.

3.8 Validity and Reliability

To ensure the validity and reliability of the research, several strategies will be implemented throughout the study.

- Validity

Validity is how successfully research evaluates its aims. This study will triangulate qualitative and quantitative data for validity. Triangulation verifies several sources to produce robust, evidence-based judgments. The researcher may check semi-structured interview findings using survey quantitative data. Also, expert peer assessment will determine validity. Child protection and research methodological experts will review the study design and procedure to ensure a sound approach, suitable data collection instruments, and rigorous analysis methods. Peer evaluation identifies study gaps and allows for changes before data collection (Tonmyr, et al., 2018).

- Reliability

Reliable research is consistent and reproducible. The study will collect data from all participants utilizing reliable interview methods and survey questions. Standardizes interviews and provides survey participants the same questions. Interviews will be transcribed and coded systematically to ensure repeatability and eliminate researcher bias. A small sample will pilot-test the survey to check question clarity, consistency, and reliability before dissemination. Before the survey is publicly disseminated, pilot test issues will be rectified.

These measures ensure validity and reliability, producing reliable research outcomes.

3.9 Conclusion

In conclusion, the Research Onion framework-guided mixed-methods approach is a flexible and resilient method for assessing child protection policy. The study uses qualitative interviews and quantitative surveys to give deep, contextual insights and wide, statistical evidence for a complete and credible research issue analysis.

CHAPTER 4: DATA ANALYSIS AND DISCUSSION

4.0 Introduction

This chapter discusses the survey and child welfare expert interviews’ principal conclusions. The complex factors that govern child welfare policy effectiveness are examined. Interagency coordination, cultural sensitivity, resource restrictions, long-term outcomes, and public awareness are key to child welfare effectiveness, according to survey data and interviews with Child Protection Officers, Social Workers, and Policymakers. These themes are essential to child protection plan creation and execution, protecting vulnerable children. The chapter details strategies to improve child welfare systems, especially in low-income communities and diverse cultures.

4.1 Survey Interpretation and analysis

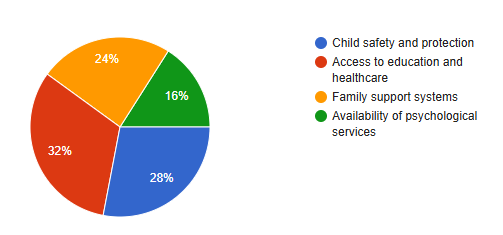

1. Which of the following are key indicators for evaluating child welfare policy impact?

Interpretation

Most respondents (32%) consider education and healthcare the most important child welfare policy indicators. Next is kid safety and protection (28%), another critical issue. Education and safety are more essential than family support networks (24%). This survey found that psychological services (16%) were the least essential, suggesting that although mental health care is appreciated, it may not be the top priority in child welfare policy.

Analysis

Child welfare prioritizes education and healthcare, maybe because good education and health are vital to children’s well-being. Children must also be safeguarded. Although safety and health services seem more crucial, family support networks are essential. The lower share for psychological services may indicate a need for mental health awareness or a focus on other welfare issues.

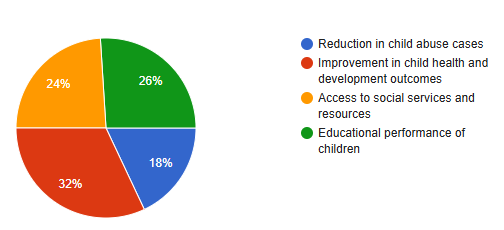

2. How should child welfare policy effectiveness be measured?

Interpretation

Most respondents (32%) say child welfare policy should be based on child health and development. Welfare policy assessment also considers children’s educational accomplishment (26%), emphasizing its importance. Access to social services and resources (24%), highlighting the need for support networks, is also significant. Child abuse decrease (18%) is the least chosen indicator, showing that although abuse prevention is essential, other criteria better measure policy performance.

Analysis

Children’s health and development are used to assess child welfare policies, showing that respondents value long-term results above immediate interventions. Academic success is especially crucial since child welfare relies on it. Children and families benefit from resources. The decreased emphasis on child abuse reduction may imply that systemic health, education, and resource improvements work better than decreasing abuse rates.

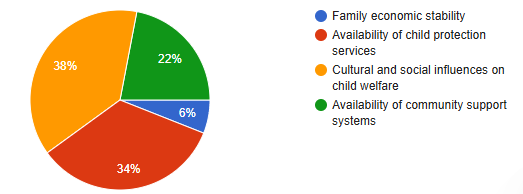

3. Which of the following factors should be considered in assessing child welfare policies?

Interpretation

Cultural and social influences on child wellbeing constitute 38% of respondents’ top policy assessment criterion. Next is Child protection service availability (34%), underlining the necessity for immediate involvement. Community networks are vital for child welfare, as 22% of community support systems matter. Family economic stability (6%) received the least attention, showing that financial difficulties are important but secondary to policy evaluation factors.

Analysis

Cultural and social variables are highly valued by respondents, indicating that successful child welfare programs must include cultural settings and community norms that enhance child well-being. Programs that focus direct child safety are crucial. Formal protection and cultural sensitivity trump community support. Low family economic stability implies respondents prefer cultural norms and professional help for child welfare.

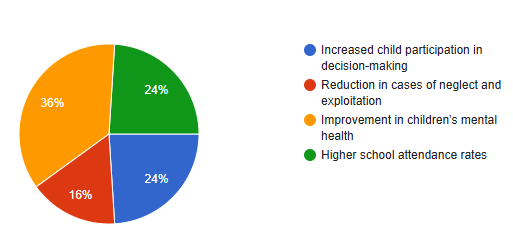

4. What is a primary indicator of a successful child welfare policy?

Interpretation

Since 36% of respondents prioritized mental health, child welfare strategies must include emotional and psychological well-being. Welfare success depends on kid engagement and education, as 24% are due to decision-making and school attendance. Despite its relevance, neglect and exploitation decrease (16%) is the least recommended indicator, showing that other successful welfare activities may reduce abuse.

Analysis

In examining child welfare programs, mental health’s importance in child development becomes obvious. Including children in welfare decisions and keeping them in school are further signs of a robust child protection system. They may choose proactive, supportive methods over neglect and exploitation reduction because they feel these results are attributable to welfare measures rather than independent evidence.

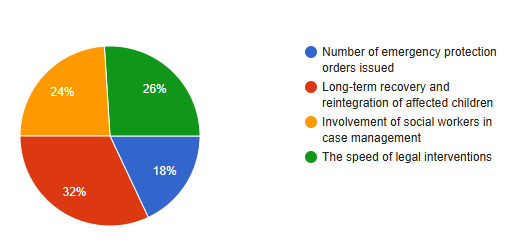

5. Which metrics are essential for evaluating the effectiveness of child protection measures?

Interpretation

The most essential criterion for judging child protection measures are long-term rehabilitation and reintegration of injured children (32%). Rapid legal interventions (26%) prioritize kid protection. Also significant is social worker engagement in case management (24%), highlighting the need for expert help. Emergency protection orders, potentially a response, are 18%.

Analysis

Child protection strategies that aid damaged children like rehabilitation and reintegration are preferred by respondents. A 26% emphasis on legal speed requires quick legal protection. Social worker engagement (24%), emphasizing child safety, is commendable. Emergency protection orders (18%) may be less significant since child protection efficacy depends on full recovery and reintegration.

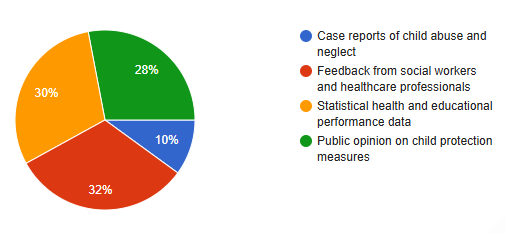

6. What type of data should be collected to evaluate child welfare policies?

Interpretation

Most respondents (32%) respect social worker and healthcare expert recommendations on child welfare policies, demonstrating the importance of professional opinions on program success. Statistical health and educational performance data (30%) shows that policy effect is measurable. Community viewpoints are important in policy evaluation, since public opinion on child protection measures (28%) follows closely. Child abuse and neglect (10%) received the least attention, maybe due to bigger figures.

Analysis

The evidence shows that policy success ratings emphasize social worker and healthcare practitioner experiences and suggestions. Child welfare evaluations need quantitative data owing to the emphasis on health and education statistics. Expert and data-driven opinions matter more than public opinion. Low priority for abuse and neglect charges reflects policy success, not direct acts.

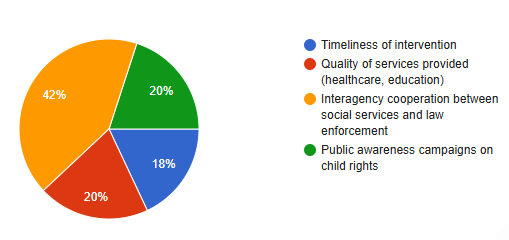

7. Which child welfare service aspect has the highest impact on policy effectiveness?

Interpretation

Most respondents (42%) believe social services-law enforcement coordination most impacts child welfare policy. This means agency collaboration is crucial to fulfilling children’s needs. Service quality (20%) and child rights awareness initiatives (20%) emphasize the need for high-quality help and informed communities. Intervention timeliness (18%) was lowest, indicating coordination and quality are more important.

Analysis

Statistics show that law enforcement and social services must collaborate to establish effective child welfare measures. To solve child welfare issues, teamwork is key. Service quality and public awareness are vital, but agency cooperation is key. The decreased emphasis on intervention time suggests that respondents prefer well-coordinated, quality services and public understanding for child welfare success. This indicates systematic, collaborative techniques.

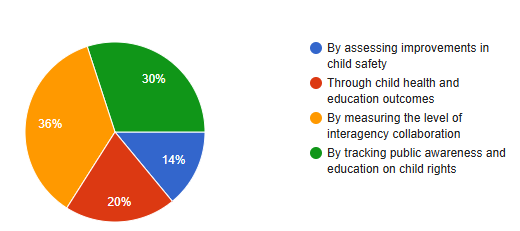

8. How can the success of child welfare policies be evaluated?

Interpretation

According to 36% of respondents, healthcare, law enforcement, and social services must work together to improve child welfare. Tracking child rights knowledge and education (30%) shows that policy efficacy needs a well-informed population. Child health and education (20%) are important but secondary to teamwork and awareness. Assessing child safety improvements had the lowest percentage (14%), showing policy effectiveness.

Analysis

Interagency collaboration is chosen for evaluating child welfare programs, showing that respondents regard cross-sector coordination highest in policy efficacy. Public awareness of child rights helps policy succeed. Health and education achievements are important but indirect success markers. The lower focus on child safety improvements implies that systemic cooperation and public awareness, not a single evaluation criterion, ensure safety.

9. Which are the most critical components for evaluating child welfare in low-income regions?

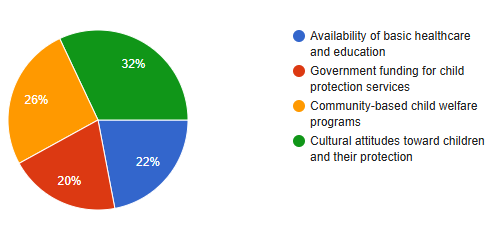

Interpretation

Most respondents (32%) consider cultural attitudes toward children and their protection the most important factor in determining child wellbeing in low-income nations, demonstrating that community norms and values strongly affect child protection. Community-based child welfare (26%), illustrating that impoverished children need local care, was also welcomed. Community culture and customs trump healthcare and education (22%). Cultural and communal factors outweighed government child protection spending (20%).

Analysis

Cultural views influence low-income child welfare assessments, highlighting the need for local culturally relevant policies. Locally oriented child welfare initiatives are essential since they focus on care. Culture and community influence healthcare and education, according to respondents. Community participation and cultural knowledge may work better in low-income communities than money when government support drops.

10. In the context of child welfare, which of the following indicators are necessary to measure the impact of policy changes?

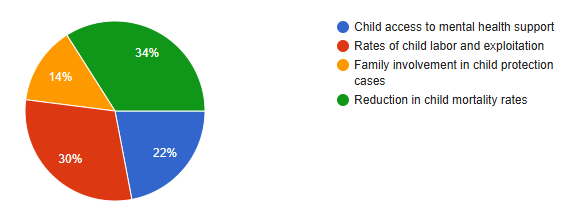

Interpretation

34% stated decreasing child death rates is the most important measure of child welfare policy changes. The 30% focus on child labor and exploitation shows that policy effectiveness relies on addressing these concerns. Childhood mental health care (22%), however, is secondary to survival and exploitation. Family contact in child protection situations (14%), despite its significance, got the least policy evaluation.

Analysis

Child welfare policy assessments focus on child survival and safety, with lower child mortality rates indicative of success. Preventing the worst forms of child abuse requires reducing child labor and exploitation. Respondents may see mental health assistance as a long-term problem rather than an immediate policy indicator given its 22% relevance. Family participation in child safety (14%), which may be a result of legislative improvements rather than a success indicator, is seldom mentioned.

4.2 Thematic analysis

4.2.1. Importance of Interagency Collaboration

Child welfare and protection need multidisciplinary collaboration, according to surveys and interviews. Interagency cooperation (42%) is the most significant feature of child welfare policy performance, the research says. This supports the premise that viable child welfare systems must include healthcare, social services, law enforcement, and education to serve vulnerable children. Child protection specialists believe these areas should work together. Fragmented services and agency cooperation harm children, according to Child Protection Officer and Policymaker interviews. The Child Protection Officer claimed inadequate communication between police, social workers, healthcare specialists, and other organizations is a serious concern. Fragmentation may delay intervention and underserve at-risk adolescents. When crucial information is delayed, vulnerable children may be left in harmful situations longer than necessary, delaying protection (Forde, 2021). Service delivery silos worry the Policymaker since the child welfare system often fails owing to lack of interagency cooperation. Each agency may do its best within its mission, but lack of coordination leads to inefficiencies and missed opportunities to act early and effectively. Healthcare staff who don’t report abuse or neglect to social services or police may delay or incompletely respond. Kid and family may not receive full aid. Effective kid protection goes beyond communication. Effective child service needs agency collaboration, resource pooling, and professional alignment. Common procedures, collaborative training, and regular communication assist professionals grasp multidisciplinary team responsibilities (Brendel et al., 2021). Integrating services across sectors helps detect and address interdisciplinary child issues including poverty, housing instability, and mental health. Without interagency cooperation, children may get inadequate care. Thus, a responsive, successful child welfare system that protects and supports vulnerable children requires interdisciplinary collaboration.

4.2.2. Cultural Sensitivity and Ethical Dilemmas

The survey and interviews focus on child care ethics and cultural sensitivity. Cultural views toward children are considered by 32% of survey respondents when analyzing child welfare legislation, especially in low-income communities. Culturally appropriate child protection activities are stressed in this conclusion. Child welfare initiatives must respect local culture and universal child safety and well-being principles to succeed. The Child Protection Officer and Social Worker noticed that cultural practices like physical punishment or hierarchical home structures conflict with child protection laws, raising ethical concerns. The Child Protection Officer highlighted that certain local cultural practices harm children yet are normal to those impacted. Physical punishment is common in several cultures. Child welfare officials consider these abuses and unlawful. This raises an ethical question: meddle and alienate the family or community, or tolerate cultural practises that harm children. The social worker underlined the difficulty of balancing child safety and cultural sensitivity in different situations (Dollee, 2021). Professionals must protect children but not impose outside standards that might damage family bonds and culture. Removing a child from their family to protect them may violate family sovereignty and cause social discord. This complexity requires a comprehensive approach that respectfully involves families, educates them on child rights, and provides culturally appropriate alternatives to harmful practices. Due to ethics, child welfare policies and procedures need cultural competence, according to interviews. Professionals must understand child protection laws and culture. Culturally sensitive child safety laws should preserve and reflect culture. Cultural variations and child safety standards must be discussed. Collaboration between child welfare organizations and local communities may help child protection specialists overcome ethical issues and ensure effective and polite interventions.

4.2.3. Resource Constraints and Systemic Barriers

The survey and interviews stress resource constraints on child welfare. Access to resources and social assistance is how 24% of respondent’s rate child welfare programs. Successful child protection programs require funding, staff, and services. Without these resources, even the finest strategies may fail. Our interviews with the Social Worker and Policymaker indicated that low funding and staff hinder child welfare program execution. High caseloads and little training and case management funds pressured the social worker. Social workers lack time and resources to address each case, delaying answers, missing treatments, and underserving vulnerable children. Care quality and child protection effectiveness suffer. Policymaker: Budget constraints also hamper child welfare program effectiveness. Child safety is important, yet many child welfare programs are underfunded, making it hard to employ and keep qualified staff, offer training, and maintain vital services. Lack of prevention and early intervention resources was a key issue. When resources are few, authorities must prioritize emergency responses above long-term abuse and neglect prevention. This reactive approach hinders child welfare policy and institutional efficiency. Interviewees said resource disparities are greater in low-income neighborhoods. There are limited child protection services, and the infrastructure may not fulfill vulnerable children’s complex needs. Child welfare involves mental health, education, and healthcare, which are scarce. The Policymaker stated that these constraints reduce child welfare programs’ immediate and long-term effectiveness and viability.

4.2.4. Focus on Long-Term Outcomes

Child welfare policy assessments are increasingly focused on long-term outcomes, according to surveys and interviews. Survey data shows that policy effectiveness is measured by children’s health and development (32%), and mental health help (22%). These results indicate a shift from short-term interventions to long-term child well-being goals. The survey respondents seem to realize that child welfare services’ efficacy is measured by their ability to permanently improve vulnerable children’s lives, not by crisis responses. Child Protection Officer and Social Worker interviews confirmed this. Child Protection Officers focused rehabilitation and reintegration for abused and neglected children. The officer thinks child welfare should prioritize immediate kid safety and long-term healing and development. It entails helping youngsters rebuild their life, reconnect with their families and communities, and find emotional and psychological recovery. The officer stated emergency protection and short-term interventions are necessary, but a child welfare system’s ability to help children overcome their past and flourish in the future is most crucial. Social Workers also emphasized mental health assistance and long-term development. Child rehabilitation, particularly trauma survivors, need mental wellness, according to the social worker (McGuire et al., 2023). Psychological treatment helps youngsters overcome trauma and form healthy relationships for their future. Without long-term support, children may struggle to cope and integrate. This move toward assessing child welfare programs based on long-term outcomes rather than short-term treatments reflects a larger awareness that child protection is about resilience and giving children the resources and support they need to live full, healthy lives. Child welfare should empower and protect children.

4.2.5. Public Awareness and Education on Child Rights

Community participation in child welfare initiatives and child rights education are stressed in the survey and interviews. Public opinion on child protection (28%) and child rights awareness (30%) are key indicators of child welfare policy impact per survey. This is a growing recognition that community knowledge and engagement are as vital as policy and law in child protection. Public kid safety education was underlined by the Policymaker in interviews. Policymaker: Without public understanding of children’s rights, efforts to protect vulnerable children may be rejected or not implemented. Public education on children’s legal rights, abuse signs, and reporting problems increases community engagement in child protection. The Policymaker stressed that awareness campaigns and educational initiatives must promote child safety as a shared responsibility, not only for government agencies or specialists. Children’s rights education allows parents, caregivers, and community members to make informed child welfare decisions (Gardner Asker, 2024). Communities learn about child rights and take action to protect children from abuse and exploitation. This community-driven strategy promotes policy effectiveness by incorporating child protection into everyday life rather than as outside interventions. Respondents also thought school-based child rights education may lead to long-term change. Early rights education may help kids protect themselves and get aid. Future generations of adults who understand and support child rights will push for and implement child protection measures in their communities.

4.3 Conclusion

This chapter concludes that child welfare policies are complicated and affected by various factors. Statistics and interviews show that child care systems must be based on agency collaboration and a deep understanding of cultural and ethical issues. Children need immediate and long-term help, but financial constraints make resource allocation challenging. Sustainable solutions promote long-term child health, development, and emotional well-being above immediate fixes. Supporting child protection requires public education on child rights. These elements must be included in child welfare initiatives to protect children immediately and provide them the tools they need to succeed.

CHAPTER 5: CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

5.0 Introduction

This chapter summarizes the research on child protection policies’ effectiveness in protecting vulnerable children, including the alignment of national policies with international frameworks, systemic challenges to their implementation, and ethical and cultural considerations. The mixed-methods study used qualitative semi-structured interviews with child protection professionals and quantitative survey data to explore operational and theoretical aspects of child protection practises across sectors (Wulczyn, et al., 2010). Resource constraints, bureaucratic inefficiencies, and ethical concerns among field workers caused policy implementation gaps, according to research. Cultural differences and inadequate interagency cooperation threatened kids. The uneven adoption of international norms like the UNCRC into national laws and practices exacerbated these concerns. Results will shape chapter suggestions to improve worldwide child protection. These ideas aim to improve child protection agencies’ efficacy, efficiency, and cultural sensitivity to support vulnerable kids.

5.1 Conclusion

This research assessed how successfully child protection policies safeguard vulnerable children, including international standards, structural issues, ethical concerns, and cultural considerations. The study used qualitative semi-structured interviews and quantitative questionnaires to examine child protection policies. The study analyzes data from legislators, social workers, and child protection officers to determine child protection law implementation barriers and their effects.

The first finding of this study was that child protection measures do not always follow international frameworks like the UNCRC. Although many states have adopted UNCRC policies, they are patchwork and ineffective. Child protection procedures vary because national laws seldom meet UNCRC obligations (Jenkins, et al., 2017). Political ideologies that prioritize local cultural norms above international standards, insufficient child safety resources, and child care institution infighting contribute to this divergence.

Lower-income states struggle to align their policies with the UNCRC. These countries lack the resources, facilities, and personnel to create successful child protection programs. This leaves children in these settings exposed to abuse, neglect, and exploitation. The analysis showed that national child protection laws cannot address structural concerns like poverty, lack of education, and inadequate healthcare, which put children at danger.

Another finding of this research is that structural issues impair child protection efforts. Underfunding is serious. Underfunded child protection agencies hinder social services’ aid for vulnerable children (Walker, 2012). Staffing, investigations, and child abuse responses are delayed due to budget issues. The results show child protection professionals get insufficient training. Child protection professionals sometimes underestimate the complexity of issues. Thus, child protection workers seldom know how to spot and treat child abuse and neglect. Social workers, police, and others may make bad decisions that damage kids.

Bureaucratic inefficiencies in child protection agencies hampered service delivery. The research says bureaucratic delays, onerous procedures, and administrative inefficiencies impede investigations and actions. Delays may endanger or neglect children. Poor interagency collaboration was another issue. Child safety requires collaboration between social agencies, police, healthcare professionals, and schools, yet they seldom interact. Missed intervention opportunities and vulnerable children result from improper coordination.

The inquiry discovered various ethical difficulties child protection practitioners face. These issues arise from parental rights and child welfare. Where a child is in risk of damage, professionals must decide whether to remove them from home, which may have legal and emotional consequences for the child and family. When a child is taken from their family without their consent, many experts worry about the long-term psychological implications.

In neglect, domestic violence, and drug addiction, protective intervention and family rights may conflict ethically. Kid protection professionals must decide whether to remove a child from a family if a parent is ignoring or abusing them due to drug or mental health issues but can care for them with support (Lukens, 2007). To balance child safety and parent rights, professionals require ethical guidelines and solid decision-making procedures.

Culture heavily affected child protection laws and practices. International child protection standards conflict with several cultures and societies. Some cultures accept physical punishment and strong parental authority, even when they violate international child abuse laws. This research indicated that child protection workers in such communities must combine cultural standards with child safety and well-being.

In nations where physical punishment is commonplace, child protection professionals struggle to implement laws prohibiting it. Child protection agencies may struggle to work with families that see child welfare as a cultural and parental right infringement. Cultural conflicts may make policy implementation difficult because families may reject interventions, causing distrust and ineffective child protection.

This study found multi-agency collaboration essential for child safety. To protect children, social services, law enforcement, education, and healthcare must collaborate. Working together helps agencies discover at-risk children and respond quickly and thoroughly. Poor communication, unclear duties, and lack of shared resources might limit collaboration. These obstacles delayed child safety measures and missed opportunities.

Many well-intentioned child safety initiatives fail due to a lack of funding and expert training, the research found. Insufficient engagement of disadvantaged communities by child protection organizations limits regulatory implementation. Ethics and culture hinder decision-making and limit protection (Wekerle, 2013).

Institutional, ethical, and cultural variables hinder child protection initiatives, says one research. These concerns must be addressed to ensure kid safety. A coordinated, comprehensive approach that blends international standards, ethics, cultural sensitivity, and multi-agency collaboration is stressed in the research. Addressing these factors is the best way to protect vulnerable children. To connect policy and practice and protect all children, governments, organizations, and child protection specialists must continually modify their rules and processes.

5.2 Recommendations

This research offers several crucial child safety policy and practice recommendations. Budget allocation, interagency coordination, professional training, and practitioners’ ethical issues are critical gaps in national policies’ international standards compliance. Addressing these gaps will increase global child safety and well-being. Politicians, child protection specialists, and organizations may overcome these problems and develop more effective and comprehensive child protection systems with these suggestions.

- Strengthening Alignment with International Standards

They advocate connecting national child protection laws with international frameworks, such as the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child. Although many states have signed the UNCRC and issued policies referencing it, implementation is patchy (Mathews, 2014). This research found that political ideology, fiscal restrictions, and cultural difficulties hamper national UNCRC implementation. The government must ensure that national child protection legislation reference and implement international frameworks. Governments should constantly assess child protection measures to identify international standards violations. Independent auditors should critically assess policies and processes. Address gaps rapidly. This may include amending national laws, increasing safeguards, or adapting systems to international child protection standards. To ensure international child protection requirements are followed, periodic assessments are needed.

- Enhancing Resource Allocation